From Foxholes to Beer Parlors

In the Service of God

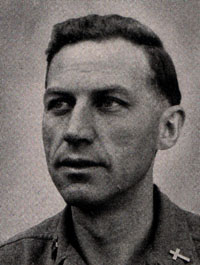

Chaplain Edward Swartout

Edward Swartout was Regimental Chaplain of the 331st Infantry. Captain Swartout served with the 83rd from Camp Atterbury, through Normandy, Luxembourg, Belgium and the Battle of the Bulge, the Rhineland, and into Germany. At the end of the war, Chaplain Swartout returned home and became pastor at a church in New Jersey. He remembers from that time that the first soldier's body returned to the US after the war was from the 83rd Division. Reverend Swartout was asked to take part in the ceremony to commemorate the return, as he had been a Chaplain with the 83rd. Edward Swartout retired from the Army with the rank of Lt. Colonel. He passed away on March 22, 2003. Thanks to Sonia (Sonny) Almond for generously allowing us to tell the story of her Father.

From the Normandy fields to the Elbe bridgeheads less than 45 miles from Berlin via the Hurtgen, the Siegfried Line, the Ardennes, had been a long and costly road to Berlin for us. Do not expect me to speak now, or ever, in glorification of war. But to these men of my Battalion, I will pay my highest respect and tribute. I salute them. They have earned a niche in the temple of fame and immortality. They never broke in the face of the enemy's fiercest counter-attacks. In these eleven months never an instance when they gave up an inch of ground they had taken. I will not praise war. I have seen it. But I will and do hail these men, both living and dead, as men of indomitable and amazing courage. Their heroic efforts and sacrifices stood betwen us all and defeat. History, I believe, will say that the margin of defeat and victory in those weeks in Normandy was exceedingly thin. History will not overlook these men nor forget to record their deeds forever.

From the Normandy fields to the Elbe bridgeheads less than 45 miles from Berlin via the Hurtgen, the Siegfried Line, the Ardennes, had been a long and costly road to Berlin for us. Do not expect me to speak now, or ever, in glorification of war. But to these men of my Battalion, I will pay my highest respect and tribute. I salute them. They have earned a niche in the temple of fame and immortality. They never broke in the face of the enemy's fiercest counter-attacks. In these eleven months never an instance when they gave up an inch of ground they had taken. I will not praise war. I have seen it. But I will and do hail these men, both living and dead, as men of indomitable and amazing courage. Their heroic efforts and sacrifices stood betwen us all and defeat. History, I believe, will say that the margin of defeat and victory in those weeks in Normandy was exceedingly thin. History will not overlook these men nor forget to record their deeds forever.

I returned to the States on September 29th at the port of Norfolk, Va., and on Oct. 4th was released from the Service at the Separation Center, Fort Dix. In the Army two years and three months, with 19 months overseas and a total of 102 points. Entire military service with the same unit, the 3rd Battalion of the 331st Infantry Regiment, 83rd Infantry Division. After long training including maneuvers in the mountains of Tennessee and Wales, the 83rd Division left Southampton for the Normandy Beach (D plus 7). We waited out a storm for almost a week in one of my most unpleasant experiences of the war. We went into the front line a few miles west of St. Lo near Carentan on June 21, 1944. We were in the Battle of the Hedgerows, a long and costly one for every Division there. Most of us were "green" troops. We were facing German Panzer and SS Divisions. There, for what seemed endless weeks, I became a medic, an "extra" evacuator of the wounded from the front to the collecting company, where ambulances carried them to the Evacuation Hospital. I prayed with and for the dying, the wounded, the living, Protestant, Catholic, and Jew alike. I held Religious Services in foxholes, five or six men in a group.

3rd Battalion (331st Infantry) aid station in France, August 1944

But to climax these more than six weeks of nothing less than "Hell on Earth," we were bombed by a German plane. It happened on the very night before the collapse of the German Defenses, called the "St. Lo Breakthrough." We (21 of us, the entire Battalion Aid Station personnel) were in a large French house. At almost exactly 12 o'clock midnight, a plane circled high, then low. We heard them coming down, not one, but three bombs. We knew (at least I felt sure I did) that they would come close. All three hit that large French house that we were in. Not one of the 21 of us was more than slightly scratched. Yet more than half of that house was destroyed. Seen in the light of morning, a miracle. All our aid station equipment buried beyond our ever reaching it. The wall of the house, next to the road, blown into that road. A bulldozer barely opened a path for vehicles after clearing debris and masonry for two hours. It had completely destroyed the very rooms next to the two we were in. We lived. Normandy and its terrific battle was over.

On the very day after this incident, we traveled a whole day. Germans had left evidence of their hurried exit. In six weeks, we had advanced some six or seven miles all told. On the day after the German plane had flattened our house, we went 20 miles in 12 hours. We went on, south then west into Brittany.

During our approach on Dinard, We'd had a hard shelling all day (in a house with no cellar in France)--when I spoke of holding service--others than Protestants volunteered. In the midst of a prayer, shelling of our area resumed, and because it was getting dusky and the fact too that most everyone was lying flat on the floor (this was a good idea at such times) I suppose some eight or ten combat engineers failed to notice anyone being in the house. They just piled in throwing themselves on the floor, surprising us by their sudden rush--and surprised themselves to find quite a few occupants ahead of them. It seemed a good time to stop praying long enough to welcome visitors. A sergeant seemed to be a spokesman for them. He said they would be quite happy to join in the Service. That with as many close ones as they'd had (and the shells were still coming in), most of them had just been doing a little praying on their own. What were these fellows? Protestant, Catholic, Jews? I didn't know them at all. They were not of my battalion, not even my regiment. They got up to leave when it was quiet. I shook hands with them, asked their name and home town. One said Schenectady I remember--practically my hometown. Into the dark they went--into the future, into the unknown dangers of the next moment, next hour, next day--outwardly the same as when they came tumbling in, but inwardly a little better fortified for the worst, even the worst that can happen to a young man.

I was in the famous old Citadel town of St. Malo while the battle raged. On August 14th, its Citadel fell. It had never fallen before under attack. Its German commandant had promised Hitler it never would while he directed. But it fell in five days. A few weeks later, the 83rd Division again caught the attention of the world. A Lieutenant with his patrol of 16 men met a German General at Beaugency Bridge on the Loire River and accepted the surrender of 20,000 Germans.

Medical officers and men in Luxembourg, November 1944

I spent a few weeks in eastern Luxembourg. We kept moving from small village to small village as we cleared the Germans from everything west of the Moselle Valley.

In early December, I went into the Hurtgen Forest a mile beyond Aachen. There I was able to prove that I had seen an axe and saw before. I was fortunate that I had. We got out of the forest and into the defenses of (and leading down to) the Roer River. On the 16th of December, we set up an aid station on the Roer River. We were closer to Berlin than the Russians. We carefully measured it. They had been a few miles closer, now we were a few miles closer than they were.

On that same night, the Germans south of us were plunging through two new, green American Divisions in the Ardennes. The Bulge, we called it. We were getting ready for Christmas, but we had little time for its celebration. In one night, we moved a hundred miles and more and met head on the German Panzers in the Ardennes. It was more than mere battle. There was snow, almost zero temperatures for weeks. I have been acclimated to very cold winters all my life in the Catskills and the cold of northern New York. I was fortunate again. The German artillery missed me and sometimes narrowly. The cold did not get me. But what the doughboy in the front line suffered is beyond description. When the history of those days of December and January is written, it will be a story of suffering and courage. It will be an Epic of American History, a story of American endurance.

Again, we went right back to the Roer River, crossed it on the last days of February, smashed across the flat Rhineland fields toward the Rhine at Dusseldorf. On the night of March 2nd, 1945 I was on the Rhine. We were the first to reach the Rhine.

I saw the first clear evidence that Germany's will to resist was breaking at last. The Rundstedt plunge had failed and they had pinned all on it. The Germans were never the same after January.

We went back to the Maas River in Holland for a short rest, and river crossing training. In the last week of March, the 9th Army crossed the Rhine. The 83rd Division and 30th Infantry Division and the 2nd Armored moved as a team due east on Berlin.

General Simpson called the 83rd the "Circus Outfit." We picked up German buses, trucks, cars, motorcycles, and rolled on over 200 miles in two weeks. We were the only American Army unit to cross the Elbe River. The entire 83rd Division crossed and put in two pontoon bridges both named in honor of the Presidents. One to the memory and honor of President Roosevelt, the other in honor of President Truman.

I dug in for a time fairly close to the Elbe. We were the only Allied troops east of the Elbe. The German tanks tried a few counter-attacks but mainly they put what was left of their Air Force in the sky at daybreak and dusk and tried their best to knock out the bridges across the Elbe. They didn't hit the bridges but the bombs came raining down, close to the bridges and close to us. They landed in the field next to me. We were very fortunate in these attacks. We surely didn't like German planes overhead. Still and all, they never did us much harm. "VE" day found us across the Elbe but the last two or three days of the war, all had been quiet. German soldiers running away from the on-rushing Russians into whose hands they least of all wished to fall.

After mid-December 1944, I was Regimental Chaplain of the 331st Infantry until July 1945, when I was transferred. For more than five months, I was without the help of a second Chaplain. It had not been easy all through the winter to cover all of the units of an entire regiment. I'd held services in foxholes, cellars, wrecked buildings, many of them churches that were almost completely demolished, and last, but not the least in the number of times used, the European Cafe and Beer Parlor.