Into the Hornet's Nest

By the beginning of August, the 83rd was part of Patton's 3rd Army, and while most of the 3rd Army turned east out of the Cotentin Peninsula toward Paris, the 83rd Division turned west into Brittany through Coutances and Avranches. The coastal towns of St. Malo and Dinard belonged to them alone.

Into the Hornet's Nest

By the beginning of August, the 83rd was part of Patton's 3rd Army, and while most of the 3rd Army turned east out of the Cotentin Peninsula toward Paris, the 83rd Division turned west into Brittany through Coutances and Avranches. The coastal towns of St. Malo and Dinard belonged to them alone.Strategically, the battle for St. Malo may not have been one of the "big battles," but that does not detract from the monumental campaign that it was. It is an incredible tale about an American commander with the improbable name of Major Speedie (329th Infantry) and a "mad" German Colonel (von Aulock)--complete with monacle, flapping coat, German Police dog, and a mysterious mistress having a "past" with Russian royalty. He said he would hold out to the last man in an ancient fortress that had been heavily reinforced with concrete and contained underground tunnels, storage areas, power plants, ammo dumps, living quarters, and even a hospital.

(The story, as told in Lee Miller's eyewitness acount, "Siege of St. Malo," Vogue Magazine, October 1944, is must reading. It is reprinted in "Reporting WWII, Part 2," published by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, NY. An even better source is "Lee Miller's War," Little, Brown and Co., Boston.The publisher has added more information and included many photographs.)

The battle for St. Malo and Dinard was incredibly complex and difficult--some might say impossible considering the heroic efforts required to conquer these heavily fortified German strongholds. Because of their strategic location along the coast, these two cities on the bay were hornet's nests of Nazi power that had been built up with fortifications even greater than those on the Normandy beaches.

The 83rd had to cross rivers, canals, ponds, swamps, and heavily fortified hills. They then fought their way through wire, mine fields, mortar and artillery fire, and machine gun crossfire from pillbox positions outside the cities. Within the cities, they had to fight house-to-house down narrow streets. And inside the fortified city of St. Malo was the Citadel itself, defended by German troops hardened in the Normandy campaign and led by a commander who vowed never to surrender.

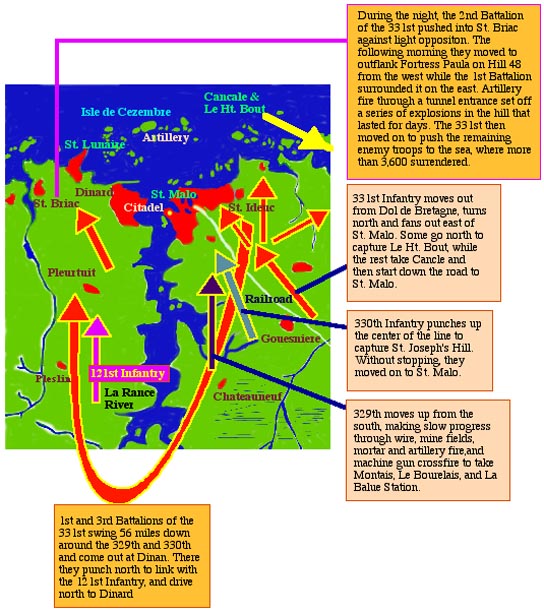

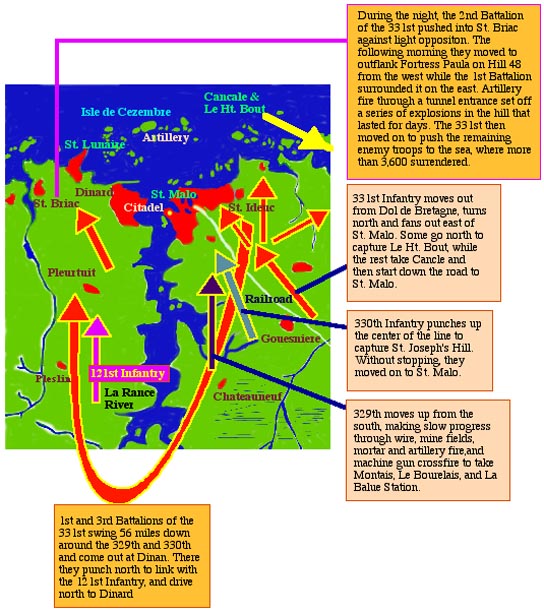

The battle for St. Malo and Dinard involved attacks on four different fronts by all three infantry regiments of the 83rd as well as the 121st Infantry Regiment of the 8th Division. Then, incredibly, in the midst of the battle, the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 331st Infantry swung around 56 miles from their position northeast of St. Malo to a position west of Dinan across the Rance River. From there, they drove north to link up with the 121st Infantry which had been cut off in a Nazi counterattack, and then continued the push to Dinard.

The battle began on 3 and 4 August, when the 83rd moved out on trucks from Feugeres to an assembly area near Pontorson. Here they started toward St. Malo and Dinard. On 4 August, the 330th, supported by the 323 Field Artillery Battalion and Division artillery, captured Dol de Bretagne and established a bridgehead over the Rau du Guiault. The 329th then passed through the bridgehead and attacked further west, capturing Miniac.

Approaches to the St. Malo peninsula were bottlenecked by canals, ponds and swamps, and increasing German resistance as the 331st moved out on the right from Dol de Bretagne along the railroad line. Bridges across the canals had been destroyed, leaving the best way to the peninsula through Chateauneuf, directly south of St. Malo. Here the 329th and Task Force A met bitter resistance from enemy forces behind and on both sides of the town.

Then all three regiments, with air and artillery support, moved out abreast against St. Malo. The 331st with the 908th Field Artillery Battalion attacked the northeastern end of the line, while the 330th with the 323rd Field Artillery attacked the center. The 329th and 322nd Field Artillery attacked on the south. The 121st Infantry was sent across the Rance via Dinan to assault Dinard.

As they moved north, riflemen in the 331st fanned out east of St. Malo and, while some of them drove north and captured Le Ht. Bout, the remainder smashed into Cancale and started down the road to St. Malo. From Cancale they could see the coastline and the immense Nazi forts with all their guns aimed uselessly at the sea.

But the Germans had other defenses. Favorable approaches toward Pointe de la Varde, St. Malo, and all along the Rance River were protected by belts of wire, minefields, and double rows of steel gates covered by fire from machine guns in hidden pillboxes. All of the approaches to the city of St. Malo were covered by prearranged artillery, mortar, and rocket fire. And big shells came whistling in from coastal guns firing from Isle de Cezembre.

The 329th moving up from the south made slow progress through wire, mine fields, mortar and artillery fire, and machine gun crossfire from pillboxes to take Montais, Le Bourelais, and La Balue Station. Then following a house-to-house assault, all of St. Servan, except the Fortress Citadel, was taken.

In the center of the line, the 330th smashed forward with artillery support from the 323rd Field Artillery, and captured St. Joseph's Hill, a high, rocky land mass where the enemy dominated the avenues of approach with murderous machine gun and mortar fire. Then, without stopping, they drove on to St. Malo.

Meanwhile, the 331st on the northeast ran into barbed wire, mines, and strong enemy fortifications east of La Mettrie. Intense gun fire from Isle de Cezembre and enemy gun boats off Pointe de la Varde further harassed their efforts. The 3rd Battalion was moved around to the center and was attached to the 330th. In bitter house-to-house fighting, they captured Parame, sealing off the enemy occupying the St. Ideuc-LaVarde area.

The capture of Dinard became imperative to prevent enemy withdrawal toward Brest. So, during the night of 9-10 August, the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 331st swept down and behind the 329th and 330th and moved across the river by way of Dinan to aid the 121st which had been cut off during a German counterattack. They drove north through the formidable Nazi defenses and broke into Pleurtuit. The attack moved rapidly against strong points consisting of more pillboxes, bunkers, and self-propelled guns. The backbone of the defense had been broken.

On August 10th at La Marchandais, a small farm about 10 km south of Dinard, the 908th Field Artillery set up its 105mm howitzers and fired directly into the fortifications at St. Malo. Fierce German counter-battery fire tore into the 908th, killing Lt. Col.Paul Thompson and three others.

The 2nd Battalion of the 330th was then attached to the 331st to make up for the 2nd Battalion of the 331st (which would join them the following day). With these reinforcements, an attack was planned to assault the heart of Dinard. The 3rd Battalion of the 331st and the 2nd Battalion of the 330th, with one battalion of the 121st Infantry, jumped off to seize the town after long artillery preparation. They drove the enemy from bunker after bunker as they forced their way into Dinard where they faced costly street fighting. Then they took St. Lunaire. The town was reported clear of enemy, but heavy fire was coming in from Hill 48 and the Isle de Cezembre in the bay.

During the night the 2nd Battalion of the 331st pushed into St. Briac against light opposition. The following morning they moved to outflank Fortress Paula on Hill 48 from the west while the 1st Battalion surrounded it on the east.

Hill 48 was an isolated hill that dominated all the terrain around it. Approaches to it were absolutely bare, with no cover. The hill was ringed in typical German style with pillboxes, all supporting each other, and mine fields. The hill itself was tunneled from end to end and was four stories high. Machine guns and 105mm guns guarded all the entrances.

The fortress contained a command headquarters, living quarters, an electric plant, air conditioning, huge stores of ammunition, food, water, and equipment of all kinds. The hill was studded with steel pillboxes and machine guns that could be fired through periscopic sights from safe positions underneath the ground. Flame-throwing booby traps were positioned along all avenues of approach. "Screaming meemies" were strung on wires to fall on troops that might reach the bottom of the hill. Some 800 fanatical German volunteers were inside, and were determined to hold out until the last round of ammunition had been fired.

One pillbox on the outer ring of the defense was captured. It was wired for communications to the Command Post deep in the center of Hill 48. A phone was connected and the enemy was demanded to surrender, which was promptly refused by the German Commandant.

Before the attack, supporting tanks and tank destroyers fired point blank at the hill. One shell smashed into a tunnel entrance, setting off nearby ammunition stores. Fire spread through the tunnels, and a white flag soon went up on top of the hill. Germans came streaming out, and those that did not survive the panic died in the tunnels with their gas masks on. For days, the hill rumbled with explosions of burning ammunition.

The 331st then moved on, pushing the remaining enemy troops to the sea--more than 3,600 surrendered, including the entire staff of the German 77th Infantry. Finally, Le Brieuc, west of Dinard, fell to the 1st Battalion of the 331st, completing the liberation of the Dinard area.

On the east side of the Rance, the 2nd Battalion of the 330th attacked strong points near St. Ideuc, and with the help of artillery support, they captured the positions and took 1,800 prisoners. The 2nd Battalion of the 329th was then attached to the 330th, and they began an assault on Ft. de la Varde, which was built on a rocky promontory with cliffs that dropped directly into the sea. On the land side, it was protected by concrete and steel bunkers, and a dense belt of mines and barbed wire. With support from Corps artillery and tank destroyers, they smashed through the enemy defenses to capture the Fort and nearly 200 prisoners.

At the same time, the 1st Battalion of the 330th, with Company L of the 331st, smashed across the causeway leading to old St. Malo. The narrow causeway was lined with buildings from which the enemy fought fiercely. A stubborn enemy force still held out in the Chateau, a huge stone medieval fort that was finally bombed and shelled into submission. All of St. Malo was finally theirs.

In St. Servan, only the Citadel remained in enemy hands. This old fort, on the end of a short, broad peninsula, dominated the bay of St. Malo and Dinard. Surrounded by thick walls, the fort had been strengthened--civilian workers said that the subterranean rooms were covered with 20 feet of solid rock.

G Company of the 329th first took the fortress of Grand Bey with 154 prisoners. Then after medium level bombardment and artillery fire, the 1st and 3rd Battalions launched a coordinated attack on the Citadel. The GIs succeeded in getting on top of the fort, but were driven back by artillery fire from Isle de Cezembre and by machine gun and mortar fire from inside the fort. Another attack was made and was again repelled.

Finally, 3-in., 155mm, and 8-in guns were placed within 2,000 yards of the fort. Direct fire slammed into the mushroom-type turrets of the Citadel and tore down part of the old wall, exposing more concrete blockhouses that, in turn, were reduced by the big guns. Finally, as fighter-bombers arrived over the target in support of a third infantry assault, Colonel Van Aulock--who had earlier refused to surrender--raised the white flag and gave up along with 571 officers and men.

This surrender is perhaps the strangest aspect of the St. Malo campaign. In a scene reminiscent of Star Wars, Lt. Col. Seth McKee dropped a 165 gallon tank of napalm through a ventilator on his first pass over the target. In McKee's words, On the date of the raid I was a Lt. Col. serving as Deputy Commander of the 370th Fighter Group. Our group was assigned to the Ninth Tactical Command which in turn was assigned to the 9th Air Force. We were stationed at La Vielle, Calvados, France (Site A-19) and were equipped with P-38s known as Lockheed Lightnings. I don't recall whether this was a group strength mission or just a squadron of which we had three. If group, it would have been either 36 or 48 aircraft. If it was a squadron mission it would have been either 12 or 16 aircraft. Whatever our strength, we were carrying napalm in 165 gallon belly tanks beneath our wings where we would normally carry our external fuel tanks. We were the first group to use napalm in Europe and used it often.

I only remember this mission as, out of 69 that I flew, it was the only one where the enemy ran up the white flag during our attack. We dropped the tanks in varying fashion depending on the target and in the St. Malo case they were delivered in a dive bombing pass which we made in two aircraft elements. Being the leader, I was the first on target with my wingman. The remainder of the aircraft were in trail behind me. The tanks were more for area targets than pinpoint targets as they were not designed to be bombs but were our normal external tanks filled with napalm in lieu of the fuel that they normally contained with phosphorus grenades attached as igniters. I guess I got lucky as my tank went down a ventilator shaft and immediately depleted all tunnels of their oxygen. When I pulled up off my target I looked back over my shoulder and observed a large white flag waving near the area of my tank's impact area. I immediately called the rest of my formation and called off the rest of the attack. At about the same time I received a call from the forward Controller requesting we call off the attack. We did so and delivered the rest of our weapons on other targets as directed.

On the ground, the entire event was witnessed by Paul Conrad who was with A Company, 308th Engineer Battalion. Paul says that he saw three P-38s fly over the Citadel and drop a single bomb into the ventilator. The planes turned around to come back, but a German waved a surrender flag and the planes left.